The phrase “80s action movie” elicits images of a musclebound Übermensch dispatching dozens of faceless enemies, all while his girlfriend/wife/daughter waits helplessly for rescue. For those who grew up with this particular genre, looking back can be tricky. On the one hand, these films provided a kind of giddy, addictive fun. At the same time, they illustrate so many things that were wrong with the era of Reagan and the Cold War—perhaps not as much as the slasher genre, but close. Their single-minded violence, lack of nuance, frequent demonization of foreigners, and almost childish misogyny cannot be shrugged away, no matter how much we love them.

Of all of these films, John Badham’s 1983 tech thriller Blue Thunder has perhaps the most complicated legacy. Unlike many other movies from the genre, Blue Thunder has a decidedly subversive message—a warning of what happens when the government, specifically the police, uses advanced technology to override the rule of law. Rather than celebrating the vigilantism and “get tough on crime” rhetoric of the era, Badham’s work actively challenges such thinking. And yet somehow, that concept became muddled in the years that followed, as a series of movies and television shows mimicked Blue Thunder while projecting the exact opposite message.

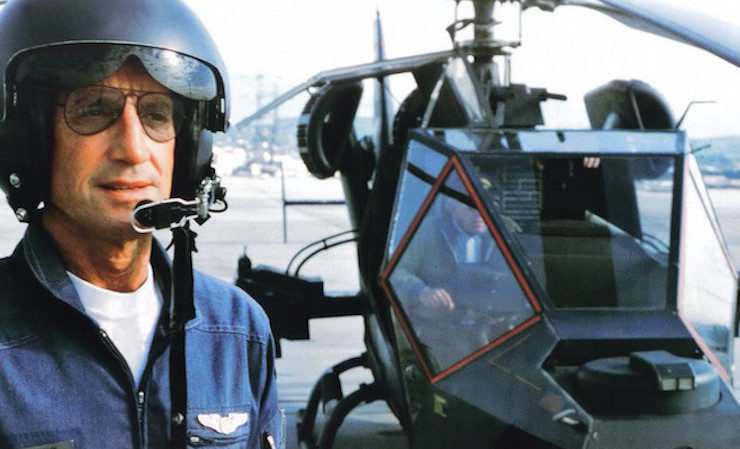

To recap the film: LAPD pilot Frank Murphy (Roy Scheider) is asked to test an experimental police helicopter. Things get complicated when he discovers the aircraft’s true purpose. Rather than merely patrolling the skies, Blue Thunder is meant to serve as an aerial gunship capable of obliterating a riot or street protest. The helicopter’s surveillance capabilities allow it to spy on anyone—an Orwellian tool the city leaders plan to exploit. For years, the investors in the project have squelched any attempt to debunk the helicopter’s effectiveness, even resorting to murder. All of this builds to a huge payoff when Murphy hijacks Blue Thunder, while his girlfriend Kate (Candy Clark) races across town to transport the incriminating evidence to the local news station. A rival pilot (Malcolm MacDowell) tracks Murphy in his own attack helicopter, leading to a climactic dogfight over the streets of Los Angeles.

Politics aside, Blue Thunder is a gem of an action flick, made with genuine care for the characters and setting, and a surprising sense of realism. Written by the great Dan O’Bannon (Alien), the script gives us a relatable protagonist struggling with his terrible memories of the Vietnam War. Scheider’s Murphy is much like Winston Smith of 1984—a government lackey, in over his head, finally opening his eyes to how dark things have become. For good measure, we also have the goofy sidekick (Daniel Stern), and the grouchy police chief (Warren Oates) who wants to do things by the book. The aerial footage combines real aircraft with miniatures, providing a tactile quality that CGI often lacks. Some of the most exciting moments involve Murphy providing air support while Kate drives her hatchback across town—not exactly a Wonder Woman moment, but at least O’Bannon gives the female lead something to do. Speaking of women, the one gratuitously 80s moment in the film involves the pilots ogling a naked yoga instructor. It is a truly tasteless, unnecessary scene that I wish was not in the final cut. If you can get past that, then the movie may be worth a rewatch.

In a behind-the-scenes documentary, O’Bannon explains his motivation for writing the script: “You’ve gotta have something you’re mad about when you sit down to write.” The ominous title card during the opening credits tells us exactly what makes him so angry: “The hardware, weaponry and surveillance systems depicted in this film are real and in use in the United States today.” Though the technology will seem clunky to modern viewers, O’Bannon correctly predicts the unsettling direction our country took in the latter years of the Cold War. The story even goes so far as to suggest that crime rates are often exaggerated by the government in order to justify higher budgets and more draconian practices. The film is most effective when it connects the militarism of the police with the hubris of American foreign policy. When Murphy is told that Blue Thunder can be used for crowd control, he scoffs: “That’s been tried before. It didn’t work then, either.” “Where was that?” he’s asked. “Vietnam,” he replies bitterly.

In an interview, O’Bannon admits that this message loses its way in the explosive third act. “Anyone who has 1984 nightmares also has a fascination with the technology,” he says. “When they tell you there’s an evil weapon, you always want to see it used.” Even if you focus on the fact that Murphy rightfully turns the weapon on its maker, the point of the climax is to show off how cool the weapon really is. [SPOILER ALERT] Though the film ends with Murphy destroying the chopper, that closing shot is muted compared to the thrilling battle sequences.

This helps explain the trend that Blue Thunder helped to perpetuate in the early 1980s. By the time the film was released, Knight Rider was wrapping its first season. In the years that followed, more super-vehicles arrived to “clean up the streets.” Almost all of them appeared in television shows that opened with the standard credit sequence, in which clips of the show are interspersed with cast members staring slightly off camera and smiling. Examples include Airwolf, Street Hawk, Riptide, Hardcastle and McCormick, Automan, and, of course, an adaptation of Blue Thunder itself. There was even a Saturday morning cartoon called Turbo Teen in which the hero becomes the car. It just wouldn’t stop.

Not only did these shows fail to capture the subversiveness of Blue Thunder, I would argue that they went in the opposite direction. The weaponry rather than the characters stood front and center, with virtually no comment on how easily such power could be abused, how quickly it could erode the moral judgment of its users. Instead of an ominous, reflective warning of government power run amok, viewers were invited to ask less nuanced questions, like, “Hey, wouldn’t it be cool if we could just shoot missiles at the bad guys?” Typically, entertainment trends result from unoriginal thinking combined with a need for ratings or ticket sales (See: Hollywood’s current reboot obsession). But one wonders about the larger implications here. It’s almost as if the arms race with the Soviet Union and the creeping paranoia of urban crime produced an insatiable demand for this kind of entertainment. Viewers needed to be assured that the heroes would eliminate the villains by any means necessary, due process be damned.

It was not until Robocop in 1987 that Hollywood produced another blockbuster action flick that delivered the same gut punch to Ronald Reagan’s America—and by then, it was more of a satire, played for laughs and shock value. A great movie, but with a decidedly less serious tone. Though, in a fitting connection, both films feature legendary TV anchor Mario Machado, delivering authoritative info dumps: the first time as tragedy, the second time as parody.

In our new world of alternative facts and permanent war, we will need more films like these—which means we’ll need to stay on the lookout for copycats that distort meaningful and original content in an effort to be “safer” and less controversial. Like Blue Thunder hovering over a sea of 80s schlock, there are a few gems out there amid the reboots and sequels. Let us find them and celebrate them. And let us demand better.

Robert Repino (@Repino1) grew up in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania. After serving in the Peace Corps in Grenada, he earned an MFA in Creative Writing at Emerson College. He works as an editor for Oxford University Press and has taught for the Gotham Writers Workshop. He is the author of Mort(e) (Soho Press, 2015), Leap High Yahoo (Amazon Kindle Singles, 2015), Culdesac (Soho Press), and D’Arc—book three in the War With No Name series, now available from Soho Press.

Robert Repino (@Repino1) grew up in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania. After serving in the Peace Corps in Grenada, he earned an MFA in Creative Writing at Emerson College. He works as an editor for Oxford University Press and has taught for the Gotham Writers Workshop. He is the author of Mort(e) (Soho Press, 2015), Leap High Yahoo (Amazon Kindle Singles, 2015), Culdesac (Soho Press), and D’Arc—book three in the War With No Name series, now available from Soho Press.